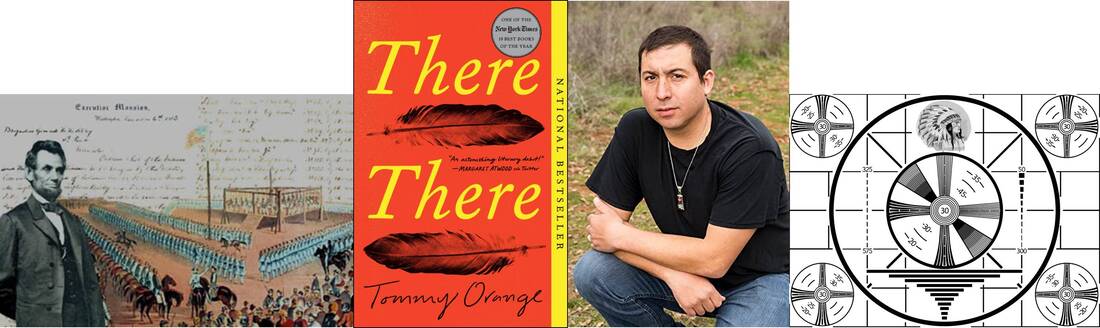

... Analyzing Tommy Orange's There ThereAs Orange shares in There There, "We made powwows because we needed a place to be together." Powwows are intertribal events, ceremonies, part of the sacred. Some have competitive activities including traditional dancing, drumming and singing. Orange said, "We keep powwowing because there aren’t very many places where we get to all be together, where we get to see and hear each other." More about powwows in excerpts from the journal article below. "We Don't Want Your Rations, We Want This Dance"The Changing Use of Song and Dane on the Southern Plains By Clyde Ellis Work Cited Orange, Tommy. "Prologue." There There. Alfred A. Knopf, 2018. 134-135. Powwow Diversified: Performance and Nationhood in Native North America, 21-23 February 2003, British Museum Author(s): Carlos David Londoño Sulkin Source: Anthropology Today, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Jun., 2003), p. 27 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3695293 Accessed: 28-11-2022 22:56 UTC "We Don't Want Your Rations, We Want This Dance": The Changing Use of Song and Dance on the Southern Plains Author(s): Clyde Ellis Source: Western Historical Quarterly , Summer, 1999, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Summer, 1999), pp. 133-154 Published by: Oxford University Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/970489 This new book will bring the Indian boarding school history to characters from his award-winning first novel.

Work Cited https://indiancountrytoday.com/news/tommy-orange-hints-about-upcoming-sequel-to-there-there |

Discussions, Journals, Articles and ReportsThis page plants truths to help root out and kill outright lies, and lies of omission, taught about American Indians, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians. Categories

All

|

|

Special Thanks

Best Friend Forever Angie Ford Advisor, American Indian Literature Dr. Zachary Laminack, Ph.D. UNCP, Assistant Professor of English Dept. of English, Theatre, and World Languages Advisor, American Indian Studies Dr. Jane Melinda Haladay, Ph.D. UNCP, Professor Dept. of American Indian Studies Dept. Chair, American Indian Studies Dr. Mary Ann Jacobs, (Lumbee), Ph.D. UNCP, Dept. Chair and Professor, American Indian Studies |

Produced by

University of North Carolina at Pembroke Students as an American Indian Studies Student Project by Best Friends Rene' Locklear White (Lumbee) and Angie Ford This Website Contains Mature Subject Matter that Every American and the World Should Know Updated 2025 |

|

Web Hosting by iPage Sanctuary on the Trail™ P.O. Box 123 Bluemont VA 20135 www.SanctuaryontheTrail.org

Hosted by Rene Locklear White www.HarvestGathering.org www.NativeFoodTrail.org www.NewTribeRising.org |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed